We are aware that using pointers for passing parameters can avoid data copy, which will benefit the performance. Nevertheless, there are always some edge cases we might need concern.

Let’s take this as an example:

|

|

Which vector addition runs faster?

Intuitively, we might consider that vec.addp is faster than vec.addv

because its parameter u uses pointer form. There should be no copies

of the data, whereas vec.addv involves data copy both when passing and

returning.

However, if we do a micro-benchmark:

|

|

And run as follows:

|

|

The benchstat will give you the following result:

|

|

How is this happening?

Inlining Optimization

This is all because of compiler optimization, and mostly because of inlining.

If we disable inline from the addv and addp:

|

|

Then run the benchmark and compare the perf with the previous one:

|

|

The inline optimization transforms the vec.addv:

|

|

to a direct assign statement:

|

|

And for the vec.addp’s case:

|

|

to a direct manipulation:

|

|

Addressing Modes

If we check the compiled assembly, the reason reveals quickly:

|

|

The dumped assumbly code is as follows:

|

|

The addv implementation uses values from the previous stack frame and

writes the result directly to the return; whereas addp needs MOVQ that

copies the parameter to different registers (e.g., copy pointers to AX and CX),

then write back when returning. Therefore, with inline disabled, the reason that addv

is slower than addp is caused by different memory access pattern.

Conclusion

Can pass by value always faster than pass by pointer? We could do a further test. But this time, we need use a generator to generate all possible cases. Here is how we could do it:

|

|

If we generate our test code and perform the same benchmark procedure again:

|

|

We could even further try a version that disables inline:

|

|

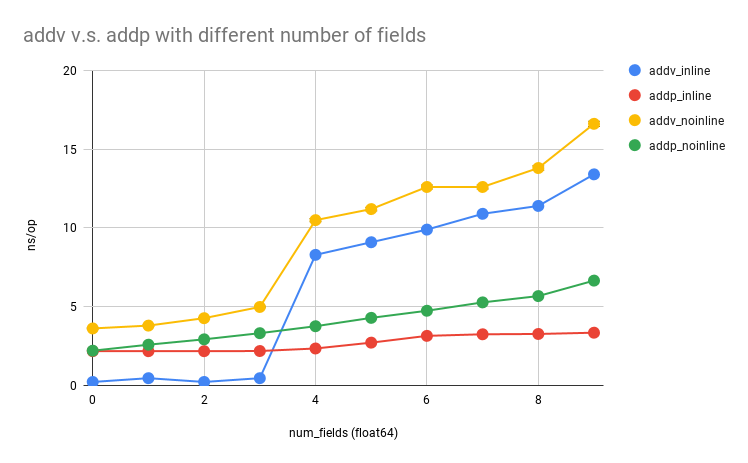

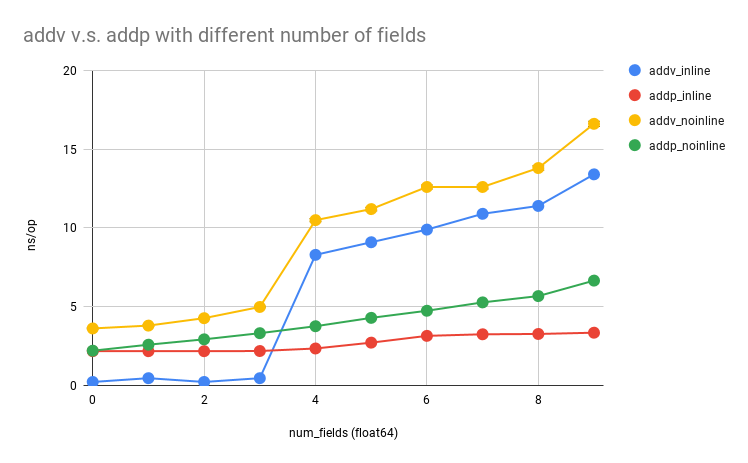

Eventually, we will endup with the following results:

TLDR: The above figure basically demonstrates when should you pass-by-value or pass-by-pointer. If you are certain that your code won’t produce any escape variables, and the size of your argument is smaller than 4*4 = 16 bytes, then you should go for pass-by-value; otherwise, you should keep using pointers.

Further Reading Suggestions

- Changkun Ou. Conduct Reliable Benchmarking in Go. March 26, 2020. https://golang.design/s/gobench

- Dave Cheney. Mid-stack inlining in Go. May 2, 2020. https://dave.cheney.net/2020/05/02/mid-stack-inlining-in-go

- Dave Cheney. Inlining optimisations in Go. April 25, 2020. https://dave.cheney.net/2020/04/25/inlining-optimisations-in-go

- MOVSD. Move or Merge Scalar Double-Precision Floating-Point Value. Last access: 2020-10-27. https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/movsd

- ADDSD. Add Scalar Double-Precision Floating-Point Values. Last access: 2020-10-27. https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/addsd

- MOVEQ. Move Quadword. Last access: 2020-10-27. https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/movq

我们都知道,使用指针传参可以避免数据拷贝,从而提升性能。然而,凡事总有例外。

来看这个例子:

|

|

哪种向量加法更快?

直觉上,我们会认为 vec.addp 比 vec.addv 更快,因为它的参数 u 使用了指针形式,不需要复制数据;而 vec.addv 在传参和返回时都会涉及数据拷贝。

然而,如果我们做一个微基准测试:

|

|

按如下方式运行:

|

|

benchstat 会给出如下结果:

|

|

这是怎么回事?

内联优化

这一切都源于编译器优化,尤其是函数内联。

如果我们对 addv 和 addp 禁用内联:

|

|

然后再次运行基准测试,并与之前的结果进行对比:

|

|

内联优化会将 vec.addv 的调用:

|

|

转换为直接赋值语句:

|

|

而对于 vec.addp 的情况:

|

|

则转换为直接操作:

|

|

寻址模式

如果查看编译后的汇编代码,原因便一目了然:

|

|

生成的汇编代码如下:

|

|

addv 的实现直接从前一个栈帧中读取值,并将结果直接写入返回位置;而 addp 则需要通过 MOVQ 将参数指针复制到不同的寄存器(例如将指针分别复制到 AX 和 CX),然后在返回时写回。因此,在禁用内联的情况下,addv 比 addp 慢的根本原因在于二者具有不同的内存访问模式。

结论

按值传参是否总比按指针传参更快?我们可以进一步测试。这次需要用一个代码生成器来覆盖所有可能的情况,做法如下:

|

|

生成测试代码并再次执行相同的基准测试流程:

|

|

我们还可以进一步尝试禁用内联的版本:

|

|

最终,我们会得到如下结果:

总结:上图清晰地展示了何时应该按值传参、何时应该按指针传参。如果你能确定代码不会产生任何逃逸变量,且参数的大小小于 4*4 = 16 字节,那么应当选择按值传参;否则,应继续使用指针。

延伸阅读

- Changkun Ou. Conduct Reliable Benchmarking in Go. March 26, 2020. https://golang.design/s/gobench

- Dave Cheney. Mid-stack inlining in Go. May 2, 2020. https://dave.cheney.net/2020/05/02/mid-stack-inlining-in-go

- Dave Cheney. Inlining optimisations in Go. April 25, 2020. https://dave.cheney.net/2020/04/25/inlining-optimisations-in-go

- MOVSD. Move or Merge Scalar Double-Precision Floating-Point Value. Last access: 2020-10-27. https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/movsd

- ADDSD. Add Scalar Double-Precision Floating-Point Values. Last access: 2020-10-27. https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/addsd

- MOVEQ. Move Quadword. Last access: 2020-10-27. https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/movq