How to create a window using Go? macOS has Cocoa, Linux has X11, but accessing these APIs seems to require Cgo. Is it possible to avoid Cgo? Some existing GUI libraries and graphics engines:

GUI Toolkits:

- https://github.com/hajimehoshi/ebiten

- https://github.com/gioui/gio

- https://github.com/fyne-io/fyne

- https://github.com/g3n/engine

- https://github.com/goki/gi

- https://github.com/peterhellberg/gfx

- https://golang.org/x/exp/shiny

2D/3D Graphics:

- https://github.com/llgcode/draw2d

- https://github.com/fogleman/gg

- https://github.com/ajstarks/svgo

- https://github.com/BurntSushi/graphics-go

- https://github.com/azul3d/engine

- https://github.com/KorokEngine/Korok

- https://github.com/EngoEngine/engo/

- http://mumax.github.io/

Here is a partial list:

https://github.com/avelino/awesome-go#gui

Most people use glfw and OpenGL. Here are some required libraries (Cgo bindings):

Some more low-level ones, e.g. X-related:

- X bindings: https://github.com/BurntSushi/xgb

- X window management: https://github.com/BurntSushi/wingo

For example, if you need Metal on macOS:

Like the GUI tool ebiten mentioned above, on Windows it no longer needs Cgo. The approach seems to be packaging the window management DLLs directly into the binary and then using DLL dynamic linking calls.

Besides GLFW, there is the heavier SDL:

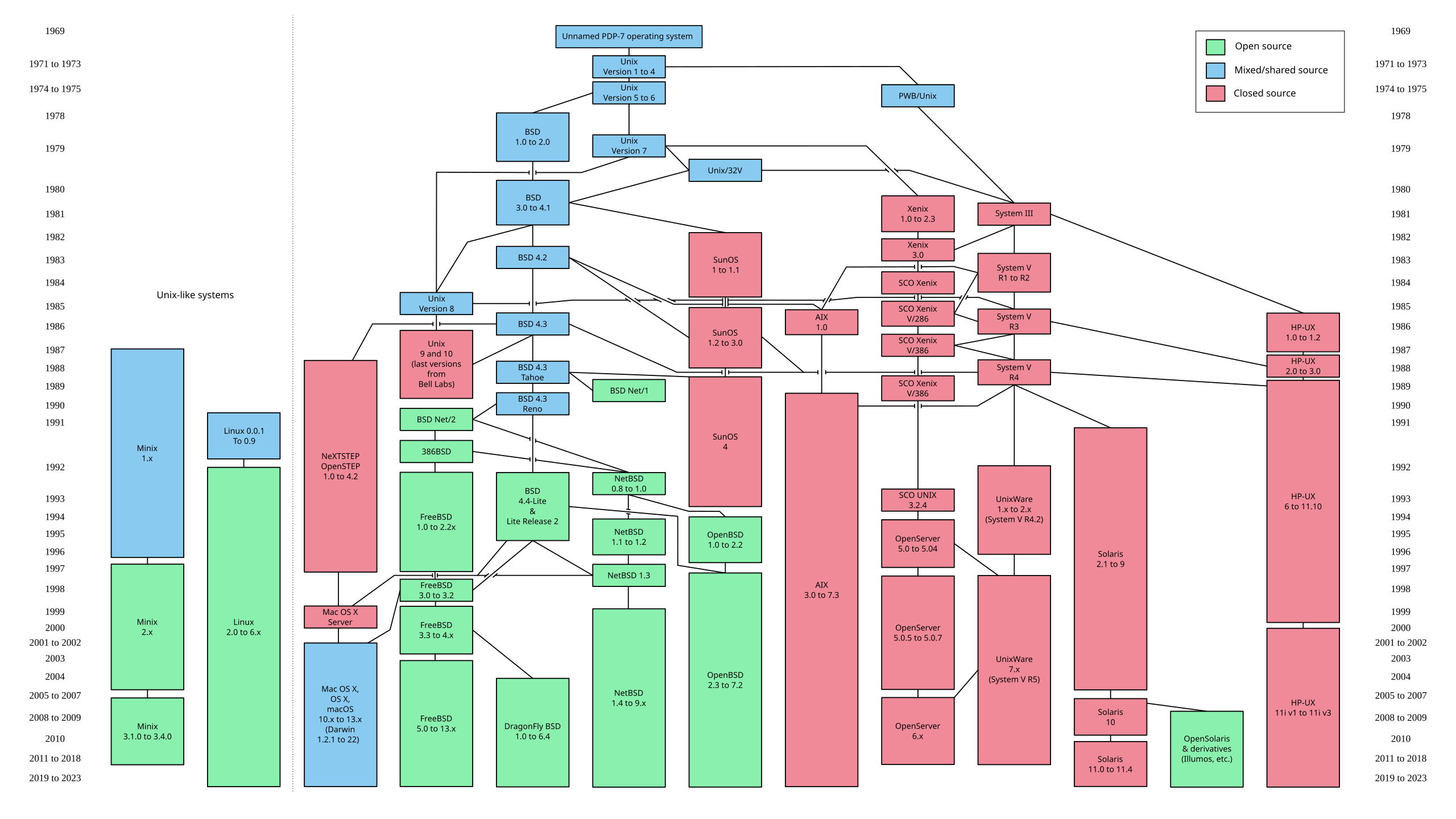

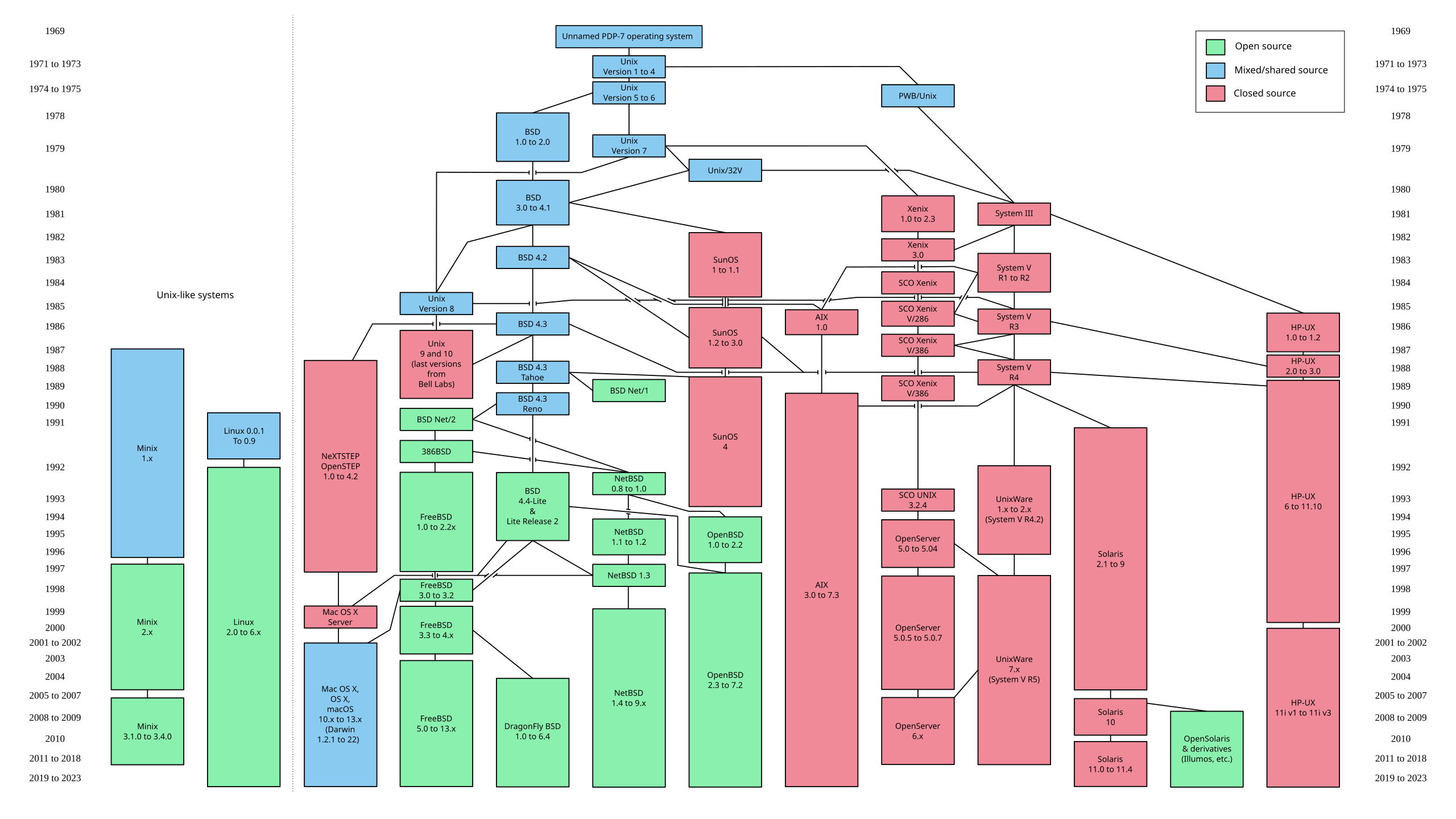

Relationships between some basic terms:

|

|

By Eraserhead1, Infinity0, Sav_vas - Levenez Unix History Diagram, Information on the history of IBM's AIX on ibm.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1801948

Relationships between some Wayland-related tools:

|

|

By Shmuel Csaba Otto Traian, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28029855

By Shmuel Csaba Otto Traian, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31768083

By Shmuel Csaba Otto Traian, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27858390

By Shmuel Csaba Otto Traian,CC BY-SA 3.0,https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27799196

So through DRM you can directly operate on the Frame Buffer under Linux, i.e., Direct Rendering Manager. Related libraries:

With this, you can do pure Go rendering directly on Linux, eliminating the dependency on C legacy.

如何使用 Go 创建一个窗口?macOS 有 Cocoa、Linux 有 X11,但访问这些 API 似乎都需要 引入 Cgo,可不可以不实用 Cgo?一些现有的 GUI 库或这图形引擎:

GUI 工具包:

- https://github.com/hajimehoshi/ebiten

- https://github.com/gioui/gio

- https://github.com/fyne-io/fyne

- https://github.com/g3n/engine

- https://github.com/goki/gi

- https://github.com/peterhellberg/gfx

- https://golang.org/x/exp/shiny

2D/3D 图形相关:

- https://github.com/llgcode/draw2d

- https://github.com/fogleman/gg

- https://github.com/ajstarks/svgo

- https://github.com/BurntSushi/graphics-go

- https://github.com/azul3d/engine

- https://github.com/KorokEngine/Korok

- https://github.com/EngoEngine/engo/

- http://mumax.github.io/

这里有一小部分:

https://github.com/avelino/awesome-go#gui

大部分人的做法是使用 glfw 和 OpenGL,这是一些需要使用到的库(Cgo 绑定):

这里面有一些相对底层一些的,比如 X 相关:

- X 绑定:https://github.com/BurntSushi/xgb

- X 窗口管理:https://github.com/BurntSushi/wingo

比如 macOS 上如果需要用到 Metal:

像是前面的 GUI 工具中的 ebiten,在 windows 上已经不需要 Cgo 了,做法似乎是将窗口管理相关的 DLL 直接打包进二进制,然后走 DLL 动态链接调用。

除了 GLFW 之外,还有相对重一些的 SDL:

一些基本名词之间的关系:

|

|

By Eraserhead1, Infinity0, Sav_vas - Levenez Unix History Diagram, Information on the history of IBM's AIX on ibm.com,CC BY-SA 3.0,https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1801948

关于 Wayland 的一些工具之间的关系:

|

|

By Shmuel Csaba Otto Traian, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28029855

By Shmuel Csaba Otto Traian, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31768083

By Shmuel Csaba Otto Traian, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27858390

By Shmuel Csaba Otto Traian,CC BY-SA 3.0,https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27799196

所以通过 DRM 可以在 Linux 下直接操作 Frame Buffer 上,也就是 Direct Rendering Manager。相关的库有:

有了这个就可以在 Linux 上直接做纯 Go 的绘制了,从而消除对 C 遗产的依赖。